Childrenswear sales within the UK market have seen a dramatic increase over the past 5 years and the industry is now believed to have an estimated worth of over £6 billion (Mintel: 2008). But within a society where most children’s clothing is purchased by adults (Jackson & Shaw, 2006, p.113) and not the children themselves, I am interested to discover what is driving this almost excessive desire to consume on their behalf? Within this essay I intend to look closely at the idea of conflicting interests within the parent/child shopping experience and how today’s retailers decide which of the two is the dominant figure when purchasing garments and therefore who to predominantly market their products to. I will also be looking at the influences of the media to determine what children deem “fashionable” and “cool” and how this is juxtaposed to how adults believe young children should dress and why. Using child theorists such as Holland and Higonnet, I intend to explore and question the idea of children “growing up too quickly” through the influence of fashion and its semiotics. From a very young age children are categorised by gender e.g. “girls wear pink and boys wear blue”, and it is this very visual segregation of the sexes that I will also be exploring in order to gain a deeper understanding of the influence that fashion has in either “protecting” or “sexualising” children within a society where sexuality is a constant danger to them.

Child theorist Patricia Holland reiterated this idea and stated that, “children pressurise their parents to buy the essential ‘toy of the year’, and advertisers exploit that ‘pester power’....kids are marvellous manipulators of parental pockets” (Holland 2004, p.67). In society today it appears that adults are having to battle with the powerful influences of the media on their children’s lives, especially within a digital age where they are constantly exposed to television, magazines, and more recently, the Internet. But within a society where this technology is now a standard within children’s lives and within easy reach, this is possibly a battle they will lose or are already losing.

Celebrity culture in the 21st Century is a highly concentrated form of representation that children are subjected to as much as adults are through the mediums of television, magazines and the internet, providing an “unrealistic” illustration of characteristics such as success and happiness. As Strasburger depicted previously, children are the most highly receptive to media influences. Images of “celebrities” within the media pose as a visual stimulus for children to latch onto, especially in the case of young girls who see highly successful and popular “stars” such as Britney Spears, as a depiction of popularity therefore someone they desire to imitate. To focus in on the idea of “idols” influencing fashions of young girls, I decided to look at the early image and reputation of Britney Spears. Her music was always intended to target the market of young girls and teenagers and her style was purposefully innocent yet with a slight sexual insinuation, manifested through a bared midriff or a short skirt. Her look and attitude were very specifically and carefully moulded in order to gain popularity within two very different but key target markets; young girls and men. As depicted within the image of Britney Spears seen in figure 3 on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine in 1999, the idea of childish innocence is overtly linked with the notion of seduction, which seems like a sinister and dangerous combination to promote. The visual idea of childhood is represented through the Telly Tubby bear she is holding close to her chest, what looks like an unbuttoned school shirt and her unrevealing cotton polka dot shorts. The sexualised aspects of the image are somewhat more obvious for example the open shirt revealing her black satin bra, the pose of Britney lying back across a pink satin sheet and her gaze towards the camera with parted lips.

Figure 3: Britney Spears, Rolling Stone magazine, 810 (1999)

Defined as the opposite of adult sexuality, childhood innocence according to Kincaid, runs the danger of becoming alluringly opposite, enticingly off-limits. Innocence suggests violation. Innocence suggests what ever adults want to imagine. If childhood is understood as a blank slate, then adults can freely project their own fantasies onto children, whatever their fantasies might be. (Kincaid cited in Higonnet 1998, p.23)

Looking specifically at the idea of children’s fashion within luxury brands, Burberry recently launched a children’s wear space within the Knightsbridge Harrods. Vogue journalist Leisa Barnett covered the story and made comments such as ‘Burberry is making it easier than ever for stylish parents to kit out their kids in next season’s finest’ and ‘Best sellers include trench coats and dresses that match the design of the men’s and womenswear collections’. Statements such as these within the media, enhanced by affirmation from adult “celebrity mum” icons such as Victoria Beckham and Katie Holmes, confirm the idea that some adults do indeed intentionally dress their children as if they an extension of their selves and their own successes (not dissimilar from the ideologies of eighteenth century childhood dress) and the retailing world have taken advantage of this by branching out previously adult-only brands into childrenswear. Also, many of today’s fashion retailers now stock their clothes in sizes as small as a 6 which enables children of 10 to wear them. This idea of the “mini-me” culture is also highly represented in Italian Vogue supplement, Vogue Bambini where children’s fashions are visually matched to influences from adult womenswear collections, informing how young girls “should” dress as shown in figure 4 below.

Their poses, tinged with attitude and prompted “sulky-pouts”, are still not reflective of the common ideal western connotations of childhood being a carefree and happy time and refer to the idea that instead they are acting out adult behaviours. Depicted within the image seen in figure 5 is a young girl wearing the designs of Italian childrenswear brand Nolita Pocket. The over-all look of the outfit is clashing and brightly coloured which connotes the idea of fun and being care-free yet the young model is wearing heavily applied eye shadow and bright red lipstick, which although matching in with the colour scheme, references back to the suggestion that these young girls being dressed up to look like young women.

Again, in figure 6 (an advert within Vogue Bambini for John Richmond) a young girl is photographed wearing a fairly non-descript black jacket and a knee-length white skirt. These items in themselves are not particularly defined as being “grown-up”, however the over-sized diamante sunglasses could be seen as being representative of today’s adult “celebrity” culture; namely associated with the image of highly publicised women such as Victoria Beckham. It is also the pose of the young girl that insinuates an adult attitude; specifically the hand in the pocket and her slouched pose and again the sulky pout, reminiscent of today’s adult models. So even if at first glance the look within Vogue Bambini is ultimately child-like (in an attempt to maintain social standards and acceptance) there are continual references to adult-like fashions and attitudes.

Referring back to the image in figure 5 of the young girl in the Nolita Pocket outfit wearing the bright red lipstick, the actual name of the brand, Nolita, also raises questions in term of its undeniably close link to the word “Lolita”.

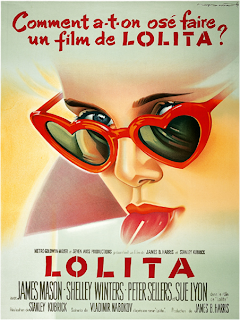

The controversial publication of Vladimir Nabokov’s “literary masterpiece” entitled Lolita in 1958 told the story of a middle-aged man lusting after a seductive young “nymphet” named Lolita and since the release of the film in 1962 and its re-make in 1997, the word has now commonly come to mean a “sexually precocious young girl”; a definition that is now recognised within the English dictionary. The highly iconic image within the film of Lolita wearing the famous red heart-shaped sunglasses and bright red lipstick (see figure 6) has become a cult movie image, but in reality it is representative of a deeply sinister and controversial subject matter brought to attention within the novel and the films.

Through the semiotics of clothing comes certain social representations and in today’s western society media influence and peer pressure are battling against a parents desire to maintain their children’s innocence for a long as possible and the key way of being able to visually display that to others is through clothing. However, the powerful force of the media is a strong contender for the attention of children. Retailers have the obvious difficulty of deciding which party to promote their products to; the responsible parent or the persuasive child. So as seen within the example of Vogue Bambini, clothing brands appear to have attempted to cater for both sets of consumers.

Written by Fashion LDN